‘Modern climate science has roots in the Hapsburg empire — it must heed marginalised voices now’

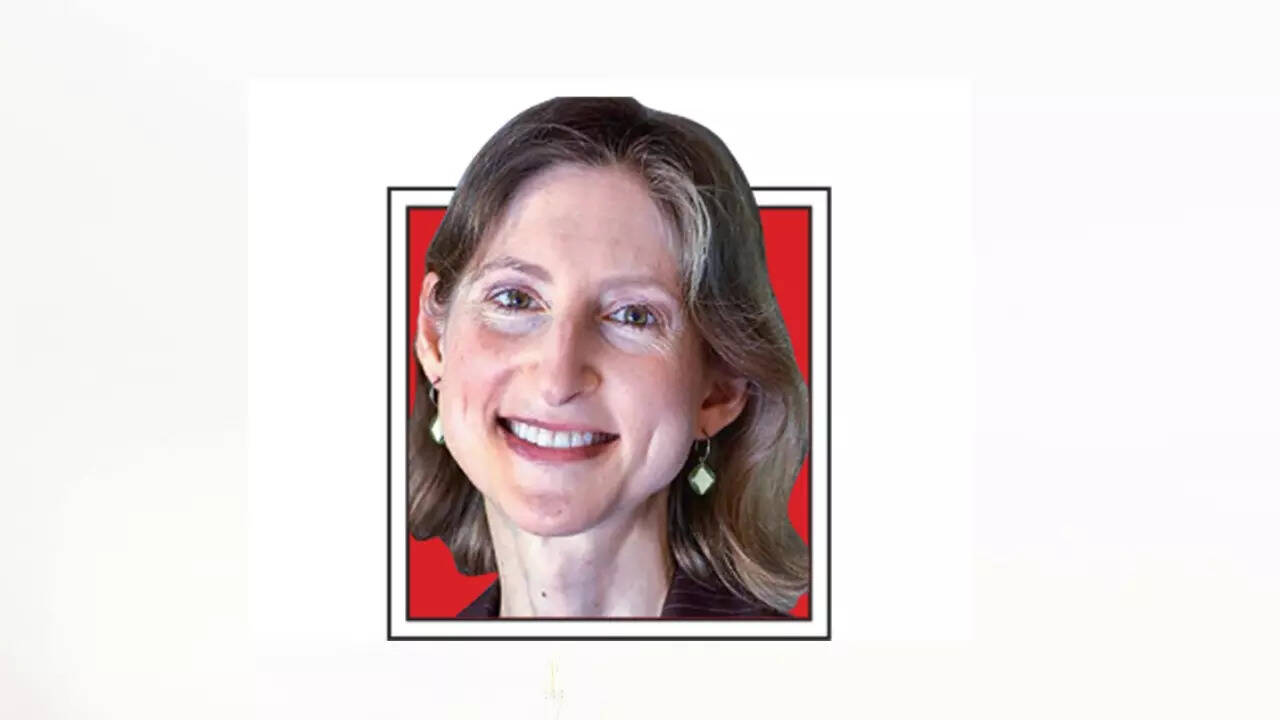

Deborah Coen is Professor and Chair of the History of Science and Medicine Program at Yale University

Deborah Coen is Professor and Chair of the History of Science and Medicine Program at Yale UniversityDeborah Coen is Professor and Chair of the History of Science and Medicine Program at Yale University. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, she discusses climate knowledge:

What is the core of your research?

■ I am currently interested in learning how scientists came to believe that human vulnerability to climate change could be measured — that principle is ensconced in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which governs climate diplomacy today. As a historian, I’d like to understand why, in the early 1990s, it seemed plausible to both scientists and policymakers that societies could be compared in terms of their susceptibility to the impacts of a changing climate.

There is in fact a long history of trying to measure the exposure of living things to a changing atmosphere — my current project turns back to the 18th century to trace efforts measuring climate vulnerability. I’m also interested in how such efforts tended to go wrong and ironically ended up idealising invulnerability.

This is problematic for today’s climate politics since no one is safe from climate change and susceptibility to it is distributed differentially across societies. That unevenness reflects a long history of colonialism, racist ideologies and the capitalist exploitation of humans and environments. I tell some of this history as a way to think about the politics of climate justice today.

Can you discuss key findings in your book ‘Climate in Motion’ which traces the scientific awareness of weather?

■ Humans have always sought a knowledge of changing seasons and their effects on plants, animals and people. I explain the origins of what we call ‘modern climate science’ — the ‘modern’ here is thought of as a global science with the capacity to analyse phenomena at a range of scales, from the planetary to the molecular.

I find this multiscalar capacity was facilitated in part by the peculiar political structure of the 19th century Hapsburg monarchy — this was a patchwork of principalities that, in the late 18th century, was increasingly centralised for economic and scientific purposes. Part of that process was the cultivation of ‘imperial royal scientists’ — these were experts on the territory of the monarchy, which stretched from the Tyrolean Alps in the west to the Hungarian plains in the east, the Carpathians in the north down to the Adriatic Sea. This presented a unique opportunity for scientists — unlike those of the British or French empires, trying to piece together data coming from far-flung places with several gaps — to have a continuous view of territory. They could see patterns which others couldn’t.

They also had a political incentive because the ideology of this monarchy was ‘unity in diversity’ — the Hapsburgs presented themselves as the guardians of the many different national and ethnic cultures under their rule. These scientists could communicate this view encompassing climate across the territory while showing variations in ecology and weather over this expanse. That produced what I call ‘dynamic climatology’, a science that could track the exchange of energy and momentum across scales — which is mathematically the foundation of modern climate science.

How were ideas about ‘temperate climates’ and social development used to justify imperialist excursions?

■ Till the late 18th century, Europeans tended to believe that climate had a determining influence on bodies and minds and these responded to the weather they lived in. At this point — coincidentally, just as a movement critical of slavery emerged — European physicians and scientists began to abandon this climatic theory of culture and turned to racial explanations, meant to legitimate the exploitation of nonwhite people in colonies. This was highly politically motivated mainstream science then.

What historical sources do you draw from in writing such history?

■ I’m interested in how knowledge of the climate has been made — and in people who aren’t considered in mainstream histories of science. I’m now studying marginalised women naturalists who made climate knowledge which wasn’t well-recognised in its own day. Women across societies were often tasked with food preparation and healthcare — these made them attentive to human vulnerabilities to climate. I’m using published writings by women naturalists, letters, fiction, poetry and art. The atmosphere, for the most, is invisible and intangible — I’m studying the creative ways women used to make this and our vulnerability to it apparent.

Climate science often remains elite, communicated largely in English — how can this be made what you call ‘usable knowledge’?

■ Climate scientists don’t necessarily know who the user of their knowledge is or what they need — an important intermediate step is to tune that research to work directly with users and let them guide the process, pose questions or set the terms.

There are exciting examples where indigenous communities are taking the lead and being empowered to build climate adaptation projects consistent with their traditions, languages and requirements. An important element of usable climate science is ensuring projects adapting to climate change recognise and respect the sovereignty and knowledge of indigenous communities, instead of only trying to impose international science on them.

What is the core of your research?

■ I am currently interested in learning how scientists came to believe that human vulnerability to climate change could be measured — that principle is ensconced in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which governs climate diplomacy today. As a historian, I’d like to understand why, in the early 1990s, it seemed plausible to both scientists and policymakers that societies could be compared in terms of their susceptibility to the impacts of a changing climate.

There is in fact a long history of trying to measure the exposure of living things to a changing atmosphere — my current project turns back to the 18th century to trace efforts measuring climate vulnerability. I’m also interested in how such efforts tended to go wrong and ironically ended up idealising invulnerability.

This is problematic for today’s climate politics since no one is safe from climate change and susceptibility to it is distributed differentially across societies. That unevenness reflects a long history of colonialism, racist ideologies and the capitalist exploitation of humans and environments. I tell some of this history as a way to think about the politics of climate justice today.

Can you discuss key findings in your book ‘Climate in Motion’ which traces the scientific awareness of weather?

■ Humans have always sought a knowledge of changing seasons and their effects on plants, animals and people. I explain the origins of what we call ‘modern climate science’ — the ‘modern’ here is thought of as a global science with the capacity to analyse phenomena at a range of scales, from the planetary to the molecular.

I find this multiscalar capacity was facilitated in part by the peculiar political structure of the 19th century Hapsburg monarchy — this was a patchwork of principalities that, in the late 18th century, was increasingly centralised for economic and scientific purposes. Part of that process was the cultivation of ‘imperial royal scientists’ — these were experts on the territory of the monarchy, which stretched from the Tyrolean Alps in the west to the Hungarian plains in the east, the Carpathians in the north down to the Adriatic Sea. This presented a unique opportunity for scientists — unlike those of the British or French empires, trying to piece together data coming from far-flung places with several gaps — to have a continuous view of territory. They could see patterns which others couldn’t.

They also had a political incentive because the ideology of this monarchy was ‘unity in diversity’ — the Hapsburgs presented themselves as the guardians of the many different national and ethnic cultures under their rule. These scientists could communicate this view encompassing climate across the territory while showing variations in ecology and weather over this expanse. That produced what I call ‘dynamic climatology’, a science that could track the exchange of energy and momentum across scales — which is mathematically the foundation of modern climate science.

How were ideas about ‘temperate climates’ and social development used to justify imperialist excursions?

■ Till the late 18th century, Europeans tended to believe that climate had a determining influence on bodies and minds and these responded to the weather they lived in. At this point — coincidentally, just as a movement critical of slavery emerged — European physicians and scientists began to abandon this climatic theory of culture and turned to racial explanations, meant to legitimate the exploitation of nonwhite people in colonies. This was highly politically motivated mainstream science then.

What historical sources do you draw from in writing such history?

■ I’m interested in how knowledge of the climate has been made — and in people who aren’t considered in mainstream histories of science. I’m now studying marginalised women naturalists who made climate knowledge which wasn’t well-recognised in its own day. Women across societies were often tasked with food preparation and healthcare — these made them attentive to human vulnerabilities to climate. I’m using published writings by women naturalists, letters, fiction, poetry and art. The atmosphere, for the most, is invisible and intangible — I’m studying the creative ways women used to make this and our vulnerability to it apparent.

Climate science often remains elite, communicated largely in English — how can this be made what you call ‘usable knowledge’?

■ Climate scientists don’t necessarily know who the user of their knowledge is or what they need — an important intermediate step is to tune that research to work directly with users and let them guide the process, pose questions or set the terms.

There are exciting examples where indigenous communities are taking the lead and being empowered to build climate adaptation projects consistent with their traditions, languages and requirements. An important element of usable climate science is ensuring projects adapting to climate change recognise and respect the sovereignty and knowledge of indigenous communities, instead of only trying to impose international science on them.

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE