‘America still uses and exports coal — mining it in Appalachia ruins forests, mountains and human health’

Michael Hendryx is professor emeritus of environmental and occupational health at Indiana University. Speaking to Times Evoke, he describes mining — and its fall-outs — in Appalachia.

Consider this tremendous paradox — one of America’s most famously beautiful regions, Appalachia, which is also scarred by the enduring ugliness and devastation of mining. It is perhaps the weight of these contradictions which makes Michael Hendryx speak with utmost gravitas about his work, pausing to balance his words — yet, conveying a heartfelt empathy. Hendryx outlines, ‘My research focuses on health disparities for people in Appalachia in the United States, concentrating specifically on communities located where mountaintop removal (MTR) occurs. This is large-scale surface coal mining and refers specifically to the physical removal of mountaintops and ridges to reach coal.’ Appalachia in the eastern US, extending from southern New York all the way down to northwestern Mississippi, holds incredibly beautiful mountains, rich temperate forests and bountiful biodiversity. Hendryx drily states, ‘Coal mining, of course, destroys these forests. Most MTR is done in central Appalachia, which is in west Virginia, Kentucky and a bit in Tennessee, some of the most rugged parts. People from northern Europe pioneered these places the 1700s onwards. Areas which had coal were mined — those places remained economically weakest.

The mining itself is strong. Hendryx describes, ‘It first involves a clear-cutting of forests. After those are destroyed, the industry uses explosives and heavy machinery to remove hundreds of feet of ‘overburden’ — topsoil and rock. They then reach the coal seams. The overburden, dumped into trucks, is moved to nearby valleys where it is literally thrown over the side. This becomes ‘valley fills’ — but these valleys contain streams, their intricate hydrology protecting water quality and supporting multiple life forms. These streams are wrecked. Research shows water quality impacted by mining thus is impaired for decades — even after the mining ends.’

Appalachia shows us how the factors that hurt Earth also hurt people. Hendryx describes the health impacts of such mining on human beings. ‘This produces air and water quality problems which people living there are exposed to. Our research has shown people located near these surface mining operations develop a variety of health disadvantages, from heart and lung disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases like bronchitis and emphysema to cancer. Children are not spared either. Our work has found a high number of birth defects in these places, from low weight at birth to heart ailments, alongside cognitive consequences like poorer academic performance which is not attribu- table to their parents’ education level or poverty. Heart defects in children in mining areas, exposed to tiny pollutants like silica, tin and iron that get into their bodies, are often 180% higher than in other regions.’

Yet, despite these shocking findings, Hendryx faced what he has described as a ‘twilight zone of denial and disbelief’. He recounts, ‘As a public health professor studying this data, I found clear scientific evidence which supported concerns people in these communities long had about their health. I published those and thought, perhaps naively, that people in charge would read the evidence and take appropriate action. But I found, to my embarrassment and surprise, that this was not the case — the coal industry attacked the science. And even the government here, elected representatives, mostly pretended they didn’t know about these impacts — they continued to support the coal industry. Today too, politicians in West Virginia get re-elected on the basis of their support for the coal industry. This continually astonishes me,’ Hendryx comments quietly.

America is considered a leader in championing clean energy though — what does it do with the coal from Appalachia? Hendryx explains, ‘Much of the coal is actually exported. We don’t use as much in the US for power generation today. We still use some though and we do export coal. But mining in these areas is in decline and we must be proactive in helping these communities transition to better futures. So far, there haven’t been large-scale, coordinated efforts to bridge these people to what comes next.’ Doing this is not an easy task, given the state of these areas. Hendryx remarks, ‘Mining actually perpetuates poverty — coal mining areas don’t have stronger economies or better job rates than other regions. Part of the underdevelopment is due to a vicious cycle these places get trapped in — think of the impairments mining does to the landscape, the destruction of forests, the polluted water, the demands on roadways by trucks moving back and forth — other industries would be reluctant to move in. Also, coal unions are not as strong as they once were. So, employees don’t have good job protection while such mining is highly mechanised, needing just a handful of workers — this suits the company, which gets coal for less labour costs, but it’s hardly good for these communities which often live just below mountain sites being exploded above their heads, polluting ecosystems and ruining their health.’

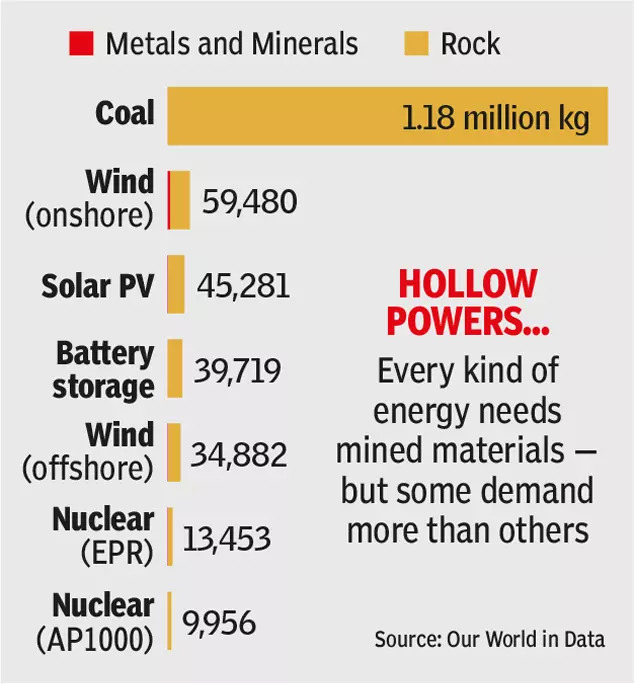

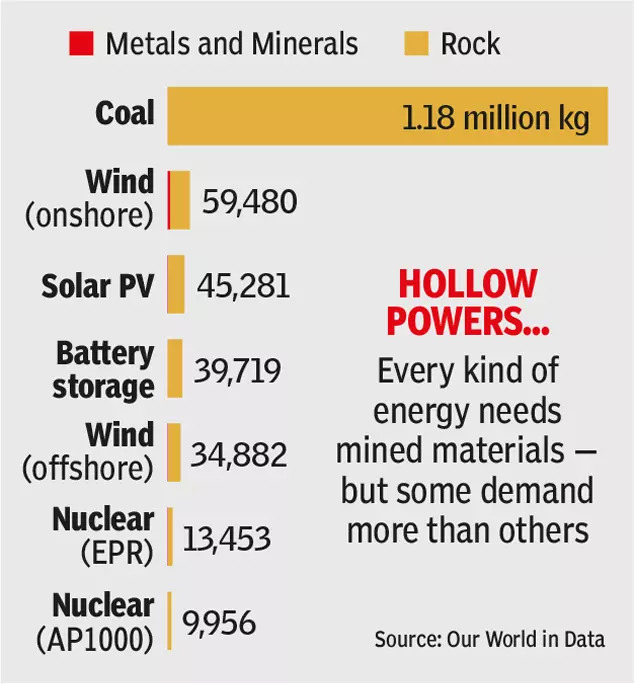

Hendryx has been focusing on developing solutions to such exposures and finding alternatives for these communities, from sustainable forestry to tourism and wind power generation, to make a better living. It is important, he feels, that we all grow more mindful about the products we use — and their links to global mining. ‘The environmental and health consequences of mining are not widely known. We need more media stories to highlight these. We also need academics to document these problems and communicate them broadly. Importantly, consumers everywhere need education — as an example, we all like electric vehicles now. But their materials need to be mined, which is polluting and uses a great deal of water. Even solar panels and wind turbines require mining. We should educate ourselves about what we buy and their effects — awareness can help us make better choices like circularity which won’t damage Earth or her people so much.’

Consider this tremendous paradox — one of America’s most famously beautiful regions, Appalachia, which is also scarred by the enduring ugliness and devastation of mining. It is perhaps the weight of these contradictions which makes Michael Hendryx speak with utmost gravitas about his work, pausing to balance his words — yet, conveying a heartfelt empathy. Hendryx outlines, ‘My research focuses on health disparities for people in Appalachia in the United States, concentrating specifically on communities located where mountaintop removal (MTR) occurs. This is large-scale surface coal mining and refers specifically to the physical removal of mountaintops and ridges to reach coal.’ Appalachia in the eastern US, extending from southern New York all the way down to northwestern Mississippi, holds incredibly beautiful mountains, rich temperate forests and bountiful biodiversity. Hendryx drily states, ‘Coal mining, of course, destroys these forests. Most MTR is done in central Appalachia, which is in west Virginia, Kentucky and a bit in Tennessee, some of the most rugged parts. People from northern Europe pioneered these places the 1700s onwards. Areas which had coal were mined — those places remained economically weakest.

The mining itself is strong. Hendryx describes, ‘It first involves a clear-cutting of forests. After those are destroyed, the industry uses explosives and heavy machinery to remove hundreds of feet of ‘overburden’ — topsoil and rock. They then reach the coal seams. The overburden, dumped into trucks, is moved to nearby valleys where it is literally thrown over the side. This becomes ‘valley fills’ — but these valleys contain streams, their intricate hydrology protecting water quality and supporting multiple life forms. These streams are wrecked. Research shows water quality impacted by mining thus is impaired for decades — even after the mining ends.’

Appalachia shows us how the factors that hurt Earth also hurt people. Hendryx describes the health impacts of such mining on human beings. ‘This produces air and water quality problems which people living there are exposed to. Our research has shown people located near these surface mining operations develop a variety of health disadvantages, from heart and lung disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases like bronchitis and emphysema to cancer. Children are not spared either. Our work has found a high number of birth defects in these places, from low weight at birth to heart ailments, alongside cognitive consequences like poorer academic performance which is not attribu- table to their parents’ education level or poverty. Heart defects in children in mining areas, exposed to tiny pollutants like silica, tin and iron that get into their bodies, are often 180% higher than in other regions.’

Yet, despite these shocking findings, Hendryx faced what he has described as a ‘twilight zone of denial and disbelief’. He recounts, ‘As a public health professor studying this data, I found clear scientific evidence which supported concerns people in these communities long had about their health. I published those and thought, perhaps naively, that people in charge would read the evidence and take appropriate action. But I found, to my embarrassment and surprise, that this was not the case — the coal industry attacked the science. And even the government here, elected representatives, mostly pretended they didn’t know about these impacts — they continued to support the coal industry. Today too, politicians in West Virginia get re-elected on the basis of their support for the coal industry. This continually astonishes me,’ Hendryx comments quietly.

America is considered a leader in championing clean energy though — what does it do with the coal from Appalachia? Hendryx explains, ‘Much of the coal is actually exported. We don’t use as much in the US for power generation today. We still use some though and we do export coal. But mining in these areas is in decline and we must be proactive in helping these communities transition to better futures. So far, there haven’t been large-scale, coordinated efforts to bridge these people to what comes next.’ Doing this is not an easy task, given the state of these areas. Hendryx remarks, ‘Mining actually perpetuates poverty — coal mining areas don’t have stronger economies or better job rates than other regions. Part of the underdevelopment is due to a vicious cycle these places get trapped in — think of the impairments mining does to the landscape, the destruction of forests, the polluted water, the demands on roadways by trucks moving back and forth — other industries would be reluctant to move in. Also, coal unions are not as strong as they once were. So, employees don’t have good job protection while such mining is highly mechanised, needing just a handful of workers — this suits the company, which gets coal for less labour costs, but it’s hardly good for these communities which often live just below mountain sites being exploded above their heads, polluting ecosystems and ruining their health.’

Hendryx has been focusing on developing solutions to such exposures and finding alternatives for these communities, from sustainable forestry to tourism and wind power generation, to make a better living. It is important, he feels, that we all grow more mindful about the products we use — and their links to global mining. ‘The environmental and health consequences of mining are not widely known. We need more media stories to highlight these. We also need academics to document these problems and communicate them broadly. Importantly, consumers everywhere need education — as an example, we all like electric vehicles now. But their materials need to be mined, which is polluting and uses a great deal of water. Even solar panels and wind turbines require mining. We should educate ourselves about what we buy and their effects — awareness can help us make better choices like circularity which won’t damage Earth or her people so much.’

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE