this story is from May 18, 2024

‘The British Raj had little knowledge — and even less sensitivity — towards animals used in war’

James Hevia is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Chicago. Speaking to Times Evoke, he describes the use of animals in imperial warfare — and times when the camels bit back:

Author of ‘Animal Labor and Colonial Warfare’, James Hevia speaks with the meticulousness of the historian, outlining facts with care to not get carried away, despite the moving quality of what he is outlining — the treatment and losses of animals in colonial warfare. Describing the difference between earlier armies’ use of animals and the imperial utilisation of these, largely in transport, he says, ‘Until the mid-19th century, the British did pretty much what the Mughals had done — they had a small number of animals attached to the army and hired local groups like the Banjaras to use bullocks and move goods across India. For the campaigns in the Sikh regions though, they began to hire and sometimes impress or force camels in as they moved to the west and northwest. They also used camels, ponies and mules in the Afghan War of 1878-1880. The Second Afghan War was a massive debacle though,’ Hevia pauses slightly, then resumes, ‘Between 60,000 to 80,000 camels perished. There was pressure from London to reform this system — yet, in 1895, came the Chitral campaign in the northwest when large numbers of animals were again lost. The government formed a committee to investigate. Under Lord Curzon, it was decided a more professionally trained transport corps would be organised — in the early 20th century, schools were set up for training. But the use of animals continued right to Independence — even afterwards, the mule component of army transport continued in India. Not long ago though,’ Hevia remarks, with a slight smile, ‘The TOI reported the Indian Army could soon stop using mules, relying instead on drones.’

INSIDE MASS DESTRUCTION: Animals were used in war before the British — but their deployment changed dramatically as the colonising force spread around the world, capturing huge tracts. The animals now faced weapons and devastation they had never seen before (Photo credit: Getty Images)

INSIDE MASS DESTRUCTION: Animals were used in war before the British — but their deployment changed dramatically as the colonising force spread around the world, capturing huge tracts. The animals now faced weapons and devastation they had never seen before (Photo credit: Getty Images)

ONLY THE HUMANS KNEW WHY: Riding horses, British soldiers battled in Africa in WWII (Photo credit: Getty Images)

ONLY THE HUMANS KNEW WHY: Riding horses, British soldiers battled in Africa in WWII (Photo credit: Getty Images)

There were even longer-lasting impacts. Canals caused waterlogging and a rise in diseases — ‘More canals meant more breeding grounds for mosquitoes which damaged camels and equines,’ Hevia describes. ‘A blood parasite locally called ‘surra’ spread among the animals via biting flies — the losses were enormous. Treatments were eventually developed but this disease remains a problem. Currently found in Asia and Africa, with climate change,’ Hevia predicts, ‘It will move to Western locations too.’

Also read: ‘Humans treat animals like slaves, taking even their flesh from them — speciesism boosts this’

The British colonial regime often presented itself as the model of order and rationality, compared to what it claimed were ‘disorderly’ native regimes before — but, Hevia says, its treatment of animals exposed this claim. He laughs dryly on hearing ‘Raj’ and ‘rationality’ together and explains why. ‘Once the British hired or forced animals into service, it was difficult to keep track of them as things were extremely chaotic. Since the British didn’t have organised units for this, they relied on civilians to handle the animals — most of the people who owned camels or mules were farmers though who didn’t want to go on these harsh campaigns. So, the British relied on ‘swee ping up the bazaars’, getting unemployed people to become animal handlers, with no experience of this. The British were not counting the animals who lost their lives in the process — they were counting how many more were needed to replace them. The effort to routinise animal use appeared and disappeared — the key element was always the cost. The point about not professionalising the transport corps was the government’s reluctance to pay for a permanent establishment, despite the large-scale perishing of animals and the costs of that. The ‘rationality’ of this depends on how you define that,’ says Hevia, with an almost imperceptible shrug.

(Photo credit: Getty Images)

(Photo credit: Getty Images)

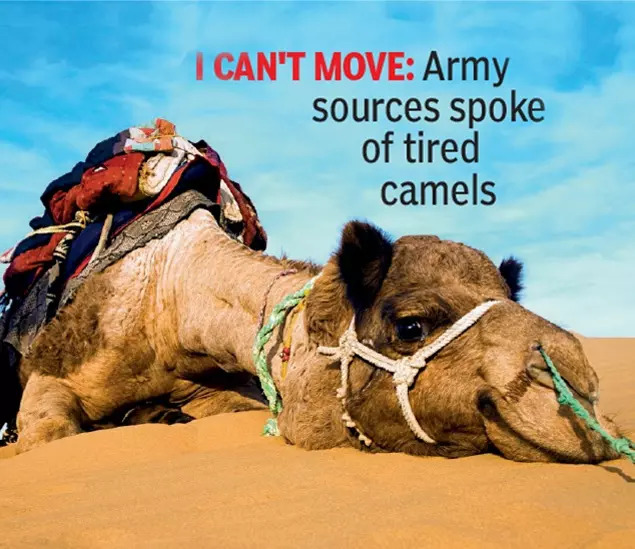

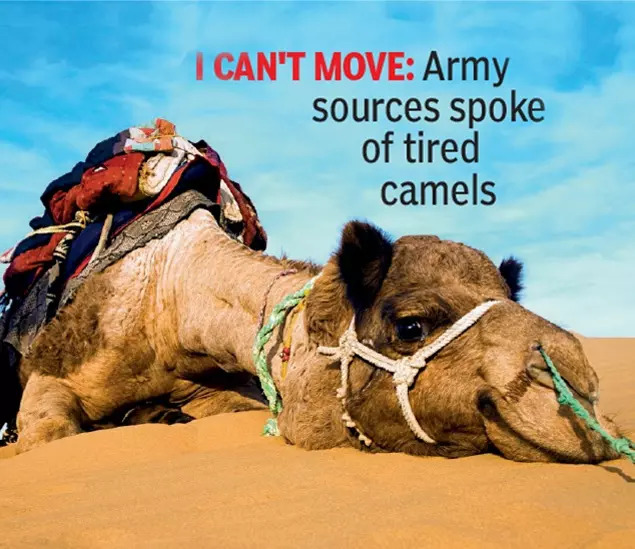

Often, there was deep obtuseness about the animals forced to go to war. ‘The British had close ties with horses but they didn’t understand camels,’ Hevia explains, ‘After many died in the Afghan War, the British said there was something wrong with the animals, not their handling of them, which was a classic case of blaming the victim. Only the rise of veterinary science exposed these flaws, recognising many camels had perished due to British ignorance.’

Also read: The beautiful & the damned

Vets became advocates for better conditions for animals, demanding more say over their treatment, often drawing from local knowledge and soldier accounts. ‘By the 20th century, more humane treatment was developing alongside greater learning,’ Hevia says. ‘One of the biggest failures in the Afghan War was overloaded camels — no-one knew the right amount they could take and arguments broke out over the load between soldiers and veterinarians.’

At times, the harried, tired animals would try to show they had some choice. ‘Camels would often refuse to move under extremely heavy loads or very difficult terrain. So did mules occasionally, although they put up with far rougher conditions,’ Hevia nods. Memoirs of the camel corps raised in the Middle East in WWI showed ties forming between the soldiers and animals, the former noting, for instance, how the camels formed strong affinity groups and didn’t like to be separated from each other. They expressed deep displeasure, with strange noises, on occasions when they were forced apart from the ones they knew. Upset by the killings or weapons or exhausted by their burdens, animals would rebel by biting or kicking. ‘Such situations needed sensitive, experienced handlers and vets with the authority to decide which animals could or couldn’t work — both came very slowly.’

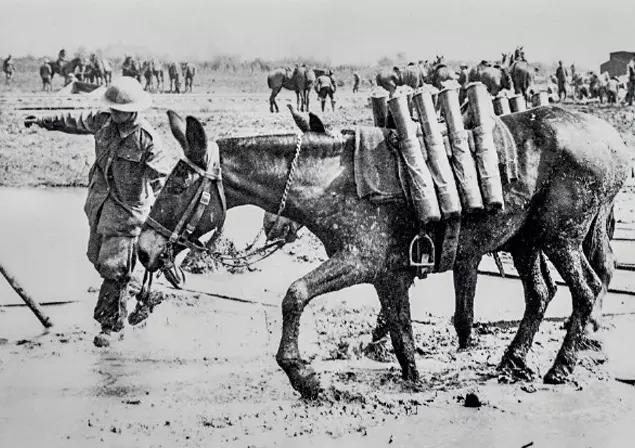

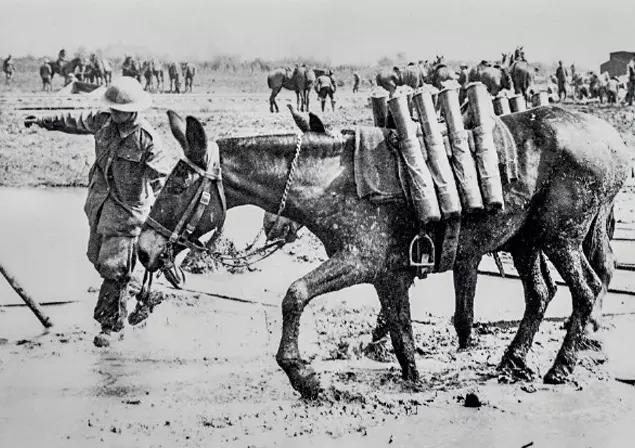

However, the treatment of animals in these wars became an issue for groups advocating animal rights. A huge number of horses were used in WWI to move supplies. They were exposed to a hithertounimagined scale of bombardment and chemical warfare. Many were in foreign lands — Hevia says, ‘In the Mesopotamia Campaign around 1915, Indian Army animals were taken and perished there. There was a growing sensibility about these losses which encompassed WWII. The animal war memorial in London acknowledges that. Vet guidebooks were also written about the proper care of animals. These,’ Hevia says, ‘Contain an echo of rights, recognising when an animal is ill-treated or overworked.’

Today, studying animal history is growing increasingly important. Hevia smiles faintly as he remarks, ‘There was a report recently about orca whales attacking ships in the Mediterranean — this could be their response to the massive rise in shipping and tour boats there. When you think about human impacts on Earth, we tend to do so primarily in terms of carbon emissions. That is only one part of the story though — the other part is animals who cannot survive beyond certain conditions. They present early warning systems of the problems we are creating on this planet. To understand the Anthropocene, we must heed the chronicles of animals.’

BEASTS OF DEADLY BURDEN: Horses had to carry artillery shells in Flanders in WWI (Photo credit: Getty Images)

BEASTS OF DEADLY BURDEN: Horses had to carry artillery shells in Flanders in WWI (Photo credit: Getty Images)

Author of ‘Animal Labor and Colonial Warfare’, James Hevia speaks with the meticulousness of the historian, outlining facts with care to not get carried away, despite the moving quality of what he is outlining — the treatment and losses of animals in colonial warfare. Describing the difference between earlier armies’ use of animals and the imperial utilisation of these, largely in transport, he says, ‘Until the mid-19th century, the British did pretty much what the Mughals had done — they had a small number of animals attached to the army and hired local groups like the Banjaras to use bullocks and move goods across India. For the campaigns in the Sikh regions though, they began to hire and sometimes impress or force camels in as they moved to the west and northwest. They also used camels, ponies and mules in the Afghan War of 1878-1880. The Second Afghan War was a massive debacle though,’ Hevia pauses slightly, then resumes, ‘Between 60,000 to 80,000 camels perished. There was pressure from London to reform this system — yet, in 1895, came the Chitral campaign in the northwest when large numbers of animals were again lost. The government formed a committee to investigate. Under Lord Curzon, it was decided a more professionally trained transport corps would be organised — in the early 20th century, schools were set up for training. But the use of animals continued right to Independence — even afterwards, the mule component of army transport continued in India. Not long ago though,’ Hevia remarks, with a slight smile, ‘The TOI reported the Indian Army could soon stop using mules, relying instead on drones.’

Animals were also involved in the British grab of what it termed ‘the canal colonies’, which had devastating ecological consequences. Hevia describes some of these, ‘The government gave land grants to people willing to raise mules or camels. Some of these in the canal colonies were directly tied to the military thus. The canals changed the ecology of Punjab. The British called the areas around the Indus ‘wastelands’ and the canals were meant to make them productive. But these were the grazing grounds of camels who needed wild plants around the rivers. Losing this natural resource, their health declined.’

There were even longer-lasting impacts. Canals caused waterlogging and a rise in diseases — ‘More canals meant more breeding grounds for mosquitoes which damaged camels and equines,’ Hevia describes. ‘A blood parasite locally called ‘surra’ spread among the animals via biting flies — the losses were enormous. Treatments were eventually developed but this disease remains a problem. Currently found in Asia and Africa, with climate change,’ Hevia predicts, ‘It will move to Western locations too.’

Also read: ‘Humans treat animals like slaves, taking even their flesh from them — speciesism boosts this’

The British colonial regime often presented itself as the model of order and rationality, compared to what it claimed were ‘disorderly’ native regimes before — but, Hevia says, its treatment of animals exposed this claim. He laughs dryly on hearing ‘Raj’ and ‘rationality’ together and explains why. ‘Once the British hired or forced animals into service, it was difficult to keep track of them as things were extremely chaotic. Since the British didn’t have organised units for this, they relied on civilians to handle the animals — most of the people who owned camels or mules were farmers though who didn’t want to go on these harsh campaigns. So, the British relied on ‘swee ping up the bazaars’, getting unemployed people to become animal handlers, with no experience of this. The British were not counting the animals who lost their lives in the process — they were counting how many more were needed to replace them. The effort to routinise animal use appeared and disappeared — the key element was always the cost. The point about not professionalising the transport corps was the government’s reluctance to pay for a permanent establishment, despite the large-scale perishing of animals and the costs of that. The ‘rationality’ of this depends on how you define that,’ says Hevia, with an almost imperceptible shrug.

Often, there was deep obtuseness about the animals forced to go to war. ‘The British had close ties with horses but they didn’t understand camels,’ Hevia explains, ‘After many died in the Afghan War, the British said there was something wrong with the animals, not their handling of them, which was a classic case of blaming the victim. Only the rise of veterinary science exposed these flaws, recognising many camels had perished due to British ignorance.’

Also read: The beautiful & the damned

Vets became advocates for better conditions for animals, demanding more say over their treatment, often drawing from local knowledge and soldier accounts. ‘By the 20th century, more humane treatment was developing alongside greater learning,’ Hevia says. ‘One of the biggest failures in the Afghan War was overloaded camels — no-one knew the right amount they could take and arguments broke out over the load between soldiers and veterinarians.’

At times, the harried, tired animals would try to show they had some choice. ‘Camels would often refuse to move under extremely heavy loads or very difficult terrain. So did mules occasionally, although they put up with far rougher conditions,’ Hevia nods. Memoirs of the camel corps raised in the Middle East in WWI showed ties forming between the soldiers and animals, the former noting, for instance, how the camels formed strong affinity groups and didn’t like to be separated from each other. They expressed deep displeasure, with strange noises, on occasions when they were forced apart from the ones they knew. Upset by the killings or weapons or exhausted by their burdens, animals would rebel by biting or kicking. ‘Such situations needed sensitive, experienced handlers and vets with the authority to decide which animals could or couldn’t work — both came very slowly.’

However, the treatment of animals in these wars became an issue for groups advocating animal rights. A huge number of horses were used in WWI to move supplies. They were exposed to a hithertounimagined scale of bombardment and chemical warfare. Many were in foreign lands — Hevia says, ‘In the Mesopotamia Campaign around 1915, Indian Army animals were taken and perished there. There was a growing sensibility about these losses which encompassed WWII. The animal war memorial in London acknowledges that. Vet guidebooks were also written about the proper care of animals. These,’ Hevia says, ‘Contain an echo of rights, recognising when an animal is ill-treated or overworked.’

Today, studying animal history is growing increasingly important. Hevia smiles faintly as he remarks, ‘There was a report recently about orca whales attacking ships in the Mediterranean — this could be their response to the massive rise in shipping and tour boats there. When you think about human impacts on Earth, we tend to do so primarily in terms of carbon emissions. That is only one part of the story though — the other part is animals who cannot survive beyond certain conditions. They present early warning systems of the problems we are creating on this planet. To understand the Anthropocene, we must heed the chronicles of animals.’

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE