- News

- entertainment

- telugu

- movies

- ‘I want to be remembered as a man who went to war without guns’

Trending

This story is from September 24, 2018

‘I want to be remembered as a man who went to war without guns’

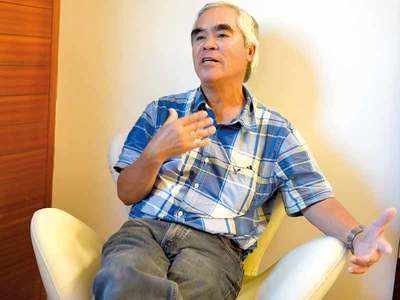

He spoke only when he was spoken to. and even when he did, his Vietnamese accented English make it difficult for people to grasp what he is saying. But no one seemed to mind. Afterall, his photographs speak a thousand words. Meet veteran war photojournalist Nick Ut, whose ‘Napalm Girl’ — a photograph of a 9-year-old Vietnamese girl running down a road, naked, screaming in pain after her village in South Vietnam was napalmed in 1972, made him a name to reckon with world over. The iconic photo became a symbol of the unimaginable horrors of the Vietnam War and won Nick Ut the prestigious Pulitzer Prize and the World Press Photo of the Year in 1973.

The iconic photo became a symbol of the unimaginable horrors of the Vietnam War and won Nick Ut the prestigious Pulitzer Prize and the World Press Photo of the Year in 1973.

It’s been 46 years, but Nick doesn’t tire of talking about capturing that tragic moment. “During the Vietnam War, rotting dead bodies on the roads and in paddy fields were a common sight, but I didn’t click them. Instead, I focused on clicking a picture that will end the war for my countrymen,” says Nick, as he settles down to speak to Hyderabad Times on the sidelines of the Indian Photography Festival.

Nick still remembers what a stir the ‘Napalm Girl’ created in the news agency he was working for in 1972. “Initially, my agency (Associated Press) was skeptical about using the picture of a naked girl. There were also people who called it ‘unethical’. I told them, ‘Look, it’s my job to capture pictures of war victims and I did it’. In fact, the then American President, Richard Nixon didn’t want to see the picture and termed it fake. But I had my witnesses — fellow photo-journalists, who were there with me when I had clicked it,” says the 67-year-old, who retired from the agency in March, 2017.

Nick says, his brother, Huynh Thanh My, a photojournalist who died at 27 while on assignment during the Vietnam War in 1965, inspired him to become a war photojournalist. “I learnt a lot about combat photography from my brother. When he used to come home after his assignments, he would show me pictures of victims. I was a 16-year-old then. when he died, I decided to become a photographer. I wanted to shoot a picture that would make my brother and my country proud,” he recalls. Soon after his brother’s untimely death, Nick joined the agency as a photographer and learnt the tricks of the trade from senior photographers such as Eddie Adams.

Nick has come a long way from that dark room in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). But he’s still in touch with the Napalm girl. “Yes. Her name is Kim Phuc and she now lives in Toronto, Canada with her family. In fact, a few months ago, she invited me to attend one of her grandkids’ wedding in Toronto. Many don’t know this, but after I clicked the picture, I took Kim to a hospital for treatment. She had suffered third-degree burns and was crying inconsolably on the way to the hospital. Now, whenever we meet we try not to talk about the war.”

There are many like Kim Phuc who are grateful to Nick for clicking that picture, which is believed to have hastened the end of Vietnam War. “In 1989, when I was sent back to the newly-formed Vietnam bureau of the agency in Hanoi, my countrymen gave me a hero’s welcome. They were proud of me because my photographs showed the true picture of the War to the world. Even in America, all the war veterans thank me for clicking ‘Napalm Girl’. They say it’s because of my picture that they are still alive and were able to return to their country from Vietnam. I consider that enough credit for me to last a lifetime,” he says, adding, “War journalism got a new meaning during the Vietnam War. It became the eyes and ears of millions of people around the world and helped shape people’s perception about the war.”

While on duty, Nick has had many brushes with death, he confesses. “I think I have been lucky that I didn’t die. I had many close calls while covering Vietnam War and was shot at three times during the war in Cambodia in 1970. Every day I would think what if today is my last day. So, I would party with my friends the night before war assignments, ’cos who knew whether or not I’d make it alive the next time I jumped out of a helicopter or a truck.”

He might have cheated death. But the scars of war persist. “You see, I was there with the soldiers amidst all the bombs, bullets and deaths. The only difference was that my weapon was a camera. Unlike soldiers who fought on a single front, I used to cover multiple fronts to get stories. Yes, I too suffered from PTSD. I used to get nightmares after the war and took professional help for it. Even today, I jump out of bed every time helicopters and planes fly over my apartment.”

It’s been 46 years, but Nick doesn’t tire of talking about capturing that tragic moment. “During the Vietnam War, rotting dead bodies on the roads and in paddy fields were a common sight, but I didn’t click them. Instead, I focused on clicking a picture that will end the war for my countrymen,” says Nick, as he settles down to speak to Hyderabad Times on the sidelines of the Indian Photography Festival.

Nick still remembers what a stir the ‘Napalm Girl’ created in the news agency he was working for in 1972. “Initially, my agency (Associated Press) was skeptical about using the picture of a naked girl. There were also people who called it ‘unethical’. I told them, ‘Look, it’s my job to capture pictures of war victims and I did it’. In fact, the then American President, Richard Nixon didn’t want to see the picture and termed it fake. But I had my witnesses — fellow photo-journalists, who were there with me when I had clicked it,” says the 67-year-old, who retired from the agency in March, 2017.

Nick says, his brother, Huynh Thanh My, a photojournalist who died at 27 while on assignment during the Vietnam War in 1965, inspired him to become a war photojournalist. “I learnt a lot about combat photography from my brother. When he used to come home after his assignments, he would show me pictures of victims. I was a 16-year-old then. when he died, I decided to become a photographer. I wanted to shoot a picture that would make my brother and my country proud,” he recalls. Soon after his brother’s untimely death, Nick joined the agency as a photographer and learnt the tricks of the trade from senior photographers such as Eddie Adams.

“Initially, I didn’t know much about the profession. I started learning from my seniors, mainly Eddie Adams. I started spending time with him in the dark room developing pictures. I got my first assignment as a war photojournalist in 1968 when the agency asked me to cover the Vietnam War.”

Nick has come a long way from that dark room in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). But he’s still in touch with the Napalm girl. “Yes. Her name is Kim Phuc and she now lives in Toronto, Canada with her family. In fact, a few months ago, she invited me to attend one of her grandkids’ wedding in Toronto. Many don’t know this, but after I clicked the picture, I took Kim to a hospital for treatment. She had suffered third-degree burns and was crying inconsolably on the way to the hospital. Now, whenever we meet we try not to talk about the war.”

There are many like Kim Phuc who are grateful to Nick for clicking that picture, which is believed to have hastened the end of Vietnam War. “In 1989, when I was sent back to the newly-formed Vietnam bureau of the agency in Hanoi, my countrymen gave me a hero’s welcome. They were proud of me because my photographs showed the true picture of the War to the world. Even in America, all the war veterans thank me for clicking ‘Napalm Girl’. They say it’s because of my picture that they are still alive and were able to return to their country from Vietnam. I consider that enough credit for me to last a lifetime,” he says, adding, “War journalism got a new meaning during the Vietnam War. It became the eyes and ears of millions of people around the world and helped shape people’s perception about the war.”

While on duty, Nick has had many brushes with death, he confesses. “I think I have been lucky that I didn’t die. I had many close calls while covering Vietnam War and was shot at three times during the war in Cambodia in 1970. Every day I would think what if today is my last day. So, I would party with my friends the night before war assignments, ’cos who knew whether or not I’d make it alive the next time I jumped out of a helicopter or a truck.”

He might have cheated death. But the scars of war persist. “You see, I was there with the soldiers amidst all the bombs, bullets and deaths. The only difference was that my weapon was a camera. Unlike soldiers who fought on a single front, I used to cover multiple fronts to get stories. Yes, I too suffered from PTSD. I used to get nightmares after the war and took professional help for it. Even today, I jump out of bed every time helicopters and planes fly over my apartment.”

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA